The discovery of gold eliminated this possibility. The sudden peopling of California by the gold rush erased the buffer of time. California filled with enough residents to qualify for statehood, and when Congress was slow to provide a government that could protect the Californians from armed robbers, arsonists and other agents of insecurity, they created a government of their own. They wrote a constitution and sent it to Washington for approval.

They also sent John C. Frémont, half of the subject of this fine new book by Steve Inskeep, as one of California’s inaugural senators. Frémont’s entry into politics was as surprising as the emergence of California, and it reflected the same forces. The bastard son of a French immigrant and his adulterous paramour, Frémont had clawed his way out of obscurity by attaching himself to powerful men. And to one woman — the other half of Inskeep’s “Imperfect Union” — even more ambitious than he.

Jessie Benton’s father had hoped for a boy. She herself often regretted being female, for it meant she would have to work twice as hard to attain anything like the influence of Thomas Hart Benton, a senator from Missouri since that state’s founding. And she would have to be crafty, for where her father could browbeat or occasionally shoot opponents, women were expected to be more demure.

Jessie met John Frémont when John escorted Jessie’s older sister to a concert. Whether the spark that resulted was passion or ambition was difficult to say. Not that either felt obliged to parse the matter; the one motive served the other. Jessie defied her father, who wanted a big wedding with a groom of good family, and eloped with John. When they broke the news and the senator ordered John to leave and never return, Jessie said she would go with him. Her will proved stronger than her father’s: Thomas Benton resigned himself to making the best of the bad situation by making the most of his son-in-law’s career

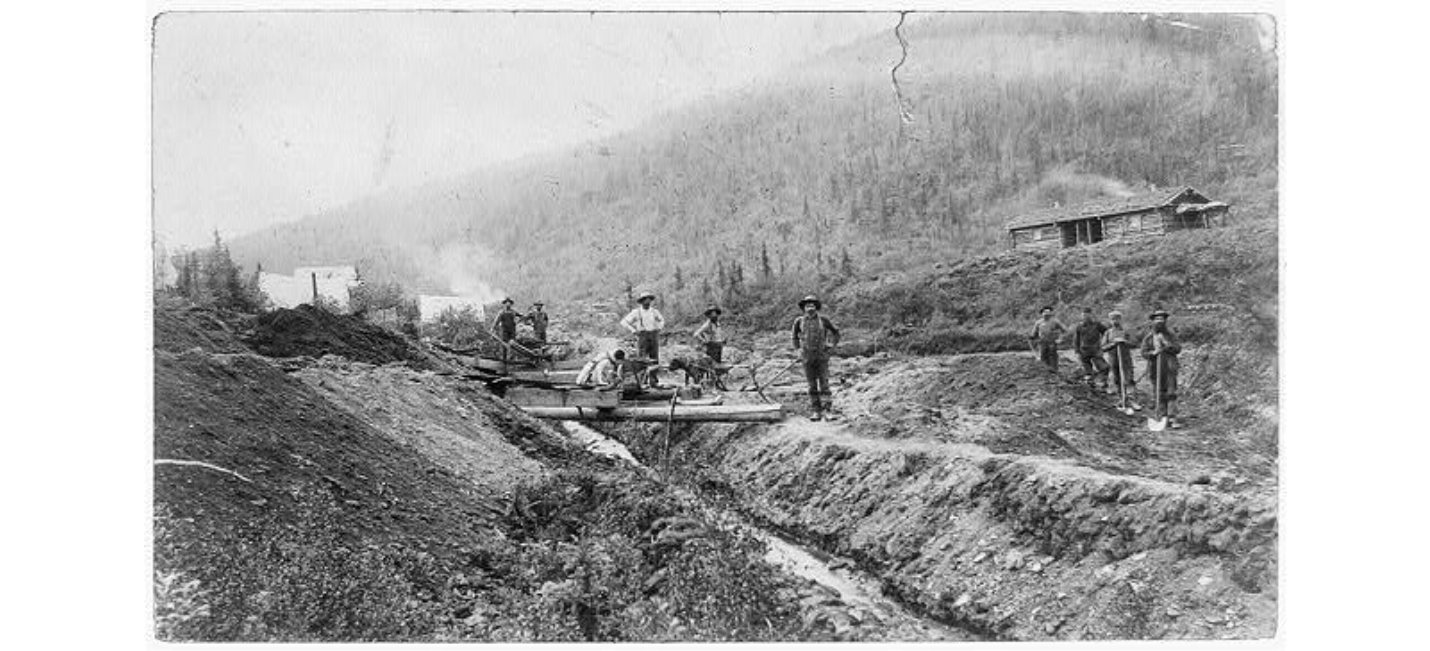

Benton’s special project was the West, which became John and Jessie Frémont’s project, too. Inskeep covered an earlier American West in his book “Jacksonland,” on Andrew Jackson and the Cherokees; in “Imperfect Union,” he follows John Frémont on various expeditions of discovery across the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin, the Cascade Range and the Sierra Nevada. Jessie Frémont is never far behind, in the telling if not the traveling, for she served as co-author, editor and promoter of the accounts that made John Frémont a hero of the armchair explorers who snatched the stirring narratives from bookshops around the country.

Inskeep’s day job is journalism; he hosts NPR’s “Morning Edition.” His journalist’s eye for detail and nuance serves his readers well. His account of the dumb luck of the Frémonts in becoming insanely wealthy in California — a property that John bought for a ranch proved to sit atop the Mother Lode — makes clear how capricious fortune could be in that singular moment of American history.

And as a journalist, Inskeep recognizes spin when he sees it. He cross-checks the Frémonts’ accounts of the Western journeys with diaries kept by other members of the expeditions, who acknowledged John Frémont’s courage but saw it shade into foolhardiness that could have killed them all. Inskeep situates the Frémont story in the context of the bluster of “Manifest Destiny,” which pronounced divine intent in American expansion. In this case, he might have discounted the rhetoric even more than he does. Then and now, it’s not obvious that anyone really took the providential formulation seriously. One of the first deliberate sound bites in American history, the slogan rationalized what people wanted to do for other reasons, without convincing skeptics.

Inskeep traces the rise of John and Jessie Frémont, culminating in his nomination for president by the new Republican Party in 1856. This narrative arc suits the author’s story of the invention of celebrity in 19th-century America. Inskeep leaves the decline to a brief epilogue. And it’s there that the Frémonts’ fate parallels that of America after the gold rush. The fight over California produced the Compromise of 1850, in which the North conceded to the South the Fugitive Slave Act in exchange for Southern acquiescence in California’s admission as a free state. The fugitive law outraged antislavery sentiment in the North and helped spawn the antislavery Republican Party, which was perceived by white Southerners as a threat to their way of life. The election of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860 triggered Southern secession and the Civil War.

Sudden wealth was a disaster for the Frémonts, too. John Frémont squandered their fortune on bad investments, eventually losing it all, and his reputation along with it. Nor did the gold do anything good for their marriage — but that might have suffered anyway, once Jessie discovered that John was out of his element in politics and would never make her the wife of a president. Imperfect union, indeed. But the more fascinating for it.

Imperfect Union

How Jessie and John Frémont Mapped the West, Invented Celebrity, and Helped Cause the Civil War

By Steve Inskeep

Penguin Press. 449 pp. $32

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)