|

THIS

COUNTY IS OPEN FOR ADOPTION.

IF

YOU WOULD LIKE TO ADOPT IT, PLEASE CONTACT THE

STATE

COORDINATOR

If you have any information to share

about Carbon County Wyoming please feel free to email me:

Rebecca

Maloney

One of the many fascinating history events

from www.wyoming.org

Three

Mixed-race Families and a Wagon Train Attack: A Story of

Frontier Survival

Published:

November 11, 2015

Bullets

splintered the wagon box. Arrows shredded the wagon’s

canvas cover. Two pregnant women huddled together in the

wagon, trying to make their toddlers lie down. The travelers

in this 12-wagon train, circled against their Lakota Sioux

attackers, were outnumbered 20 to one and losing fast.

Then,

from the meager protection of the wagons, one of the women,

eight months pregnant and impeded by her bulk, strode out

into the midst of the battle. She had recognized some of the

attackers—she knew them personally. She shouted at the

Indians to stop their attack or her brother, their own

Hunkpapa Sioux war chief, Gall, would take vengeance.

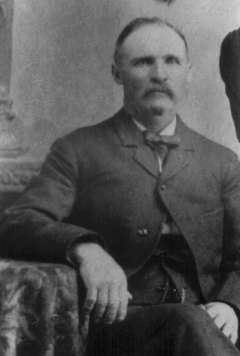

Illustration

1: Woman Dress Lamoreaux some years after her courage saved

her family's lives when their wagon train was attacked near

Split Rock. Lander Pioneer Museum.

Woman

Dress Lamoreaux and her relatives

At

the time of the attack, the travelers were near Split

Rock on

the Oregon Trail, about a day’s travel west of Devil’s

Gate in what’s now central Wyoming.

How

did one of their attackers’ own people, Woman Dress

Lamoreaux, come to be in this wagon train on the way

from Fort

Laramie to

the South

Pass area

in March and April 1868? It was an atypical group: Of the

26-member party, about half were American Indians,

mixed-bloods or white men who had married Indians.

In

the early and mid-1800s, many white traders—often

French-speaking, with roots in French Canada or the

Mississippi Valley—married Cheyenne,

Sioux and Shoshone women, gaining important business

alliances by these unions. At least three such extended

families were traveling in this wagon train.

The

most prosperous member of the wagon train was Fort Laramie

trader Jules Lamoreaux; five of the 12 wagons were his.

Lamoreaux was born in Canada at Hyacinthe, Quebec, in 1836.

He worked at Fort Laramie for James Bordeaux before opening

his own store there, marrying Woman Dress in 1862. At the

time of the 1868 journey to South Pass, they had two

children, Lizzie and Richard, ages about 5 and 3.

The

Lajeunesses

The

largest group was the clan of Charles Lajeunesse, also known

as Seminoe, who operated a trading post at Devil’s

Gate from 1852 to 1856, and at other times and points along

the Oregon Trail. Lajeunesse's grown, half-Shoshone sons,

Mich, Noel and Ed, were escorting their pregnant younger

sister, Louisa Lajeunesse Boyd, along with her husband,

William Henry Harrison Boyd, and their daughter, Martha,

approximately 3 years old. Boyd was from Tennessee and had

come west in about 1859 where he worked for and was educated

by Charles Lajeunesse, eventually becoming his partner, and

marrying his daughter about 1864.

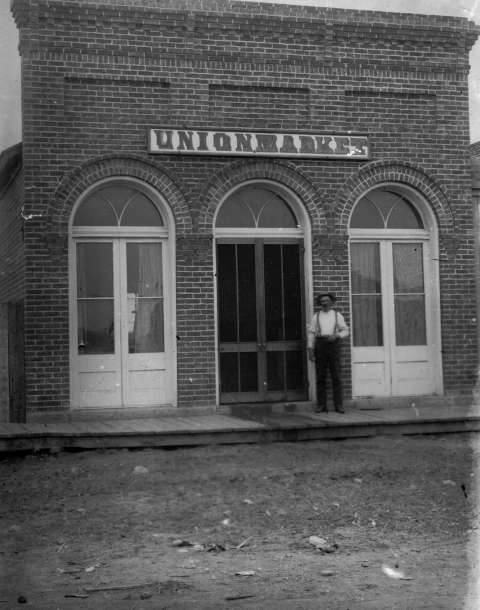

Illustration

2: The prosperous Jules Lamoreaux, Canada-born Oregon Trail

trader, owned five of the 12 wagons attacked on the trail

in 1868. He and his Sioux wife, Woman Dress, eventually had

17 children--the third of whom, Willlow, was born near

South Pass a week or so after the attack. Lander Pioneer

Museum.

Mich

and Noel had fought at the July 1865 Battle of Platte Bridge

near present Casper,

Wyo., where Mich killed High Backed Wolf, a Cheyenne chief.

High Backed Wolf had killed their father a few weeks

previously, and Louisa and the other Shoshone women at

Platte Bridge celebrated this revenge by dancing and

singing, wearing High Backed Wolf's scalp-decorated,

bloodstained shirt.

The

Ecoffeys

Yet

another mixed-blood couple, Julia Bissonette Ecoffey, a

half-Sioux, and her husband Frank Ecoffey, were also with

this expedition. Julia's father, Joseph Bissonette, was a

trader, government interpreter and partner of Charles

Lajeunesse and William Boyd on Deer Creek about 1864.

Bissonette had been in the trading business along the trails

at least since 1842, when he had accompanied the explorer

John C. Fremont as an interpreter from Fort Laramie to Red

Buttes near

present Casper. Ecoffey, a French-Swiss, arrived at Fort

Laramie in 1855, clerking for Bissonette and Lajeunesse in

the early 1860s. In 1865, about two years before he married

Julia, he had a store at Platte Bridge and helped defend it

during the battle that July.

Survival

in a fast-changing world

All

of these mixed-blood families had been established at Fort

Laramie before deciding to move to the area of South Pass,

planning to set up business near the soon-to-be-booming

gold camps where

significant finds had been made in 1867. Once-profitable

trade with Indians and with white emigrants was waning.

Illustration

3: Jules Lamoreaux in front of his butcher shop, one of the

first brick buildings in the new town of Lander, 1870s.

Lamoreaux served as Lander's second mayor. Lander Pioneer

Museum.

The Union

Pacific Railroad, building

west, spawned towns and stores filled with cheap

manufactured goods that cut into the traders' business. As

buffalo herds dwindled, many Indians had become impoverished

and were settling on the reservations, or were increasingly

hostile—especially the Sioux and Cheyenne—as

they chose to defend their lands. These were the years

of Red

Cloud’s War along

the Bozeman

Trail to the northeast,

and of many raids and skirmishes along the Oregon and

Overland trails across what’s now Wyoming.

|