|

THIS

COUNTY IS OPEN FOR ADOPTION.

IF

YOU WOULD LIKE TO ADOPT IT, PLEASE CONTACT THE STATE

COORDINATOR

If you have any information to share

about Carbon County Wyoming please feel free to email me:

Rebecca

Maloney

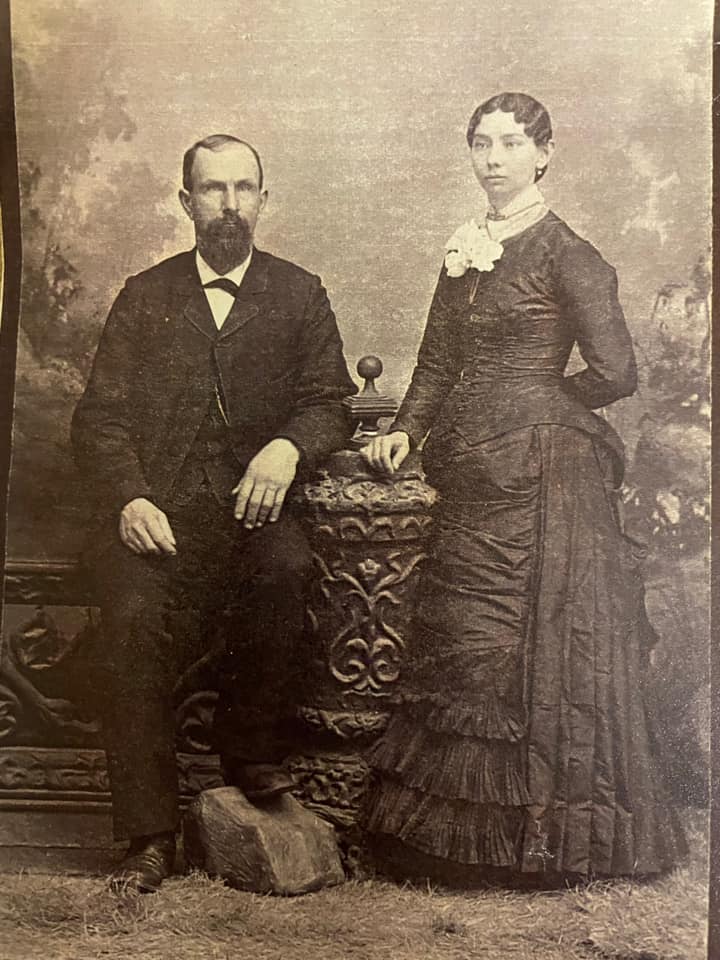

George and Julia Childs

Ferris

When most people talk about

George Ferris, its usually about how he came

out west as a game hunter for the Wells

Fargo Stage Coach Company and the Union

Pacific Railroad, settled in Rawlins, got

into mining copper, made millions,

commissioned one of the most significant

Queen Ann Style mansions in Wyoming to be

built here in Rawlins, and passed away

before he could move into it with his

family.

But did you know that before

George came to Rawlins he had fought in the

Civil War?

George Ferris was born in

Eaton Rapids Michigan on January 21st 1840.

He grew up in that town living a modest life

and developing a love of riding horseback.

On April 12th 1861 Civil War broke out

in the United States splitting the country

in two. Being in Michigan, George was fairly

well removed from the war, however

eventually he could no longer sit back and

read headlines in the news paper. He decided

he had to take action and make his

contribution to the war effort.

On

September 9th 1862 at the ripe old age of

22, George enlisted into the Union Cavalry.

When he enlisted he was given the rank of

Corporal, but in less than a year, on June

26th 1863, he was promoted to Sergeant.

George served with the 7th Michigan Cavalry

in Company D. The 7th Michigan Cavalry

Regiment was a part of the famed Michigan

Brigade, commanded for a time by Brigadier

General George Armstrong Custer. This

regiment would have seen the Battle of

Gettysburg, Kilpatrick's Raid on Richmond,

Battle of the Wilderness, Battle of Yellow

Tavern, Battle of Cedar Creek, Battle of

Five Forks, and Appomattox.

George was

mustered out on October 6th 1865, and so was

set on his path that would bring him to

Rawlins Wyoming.

The Ferris

Mansion 607 W Maple St, Rawlins, WY 82301

The Ferris Mansion in Rawlins is both a

sad and an inspiring tale all wrapped into

one.

George Ferris had for his whole

life pursued great wealth. On the very day

he achieved it by selling the Ferris-Hagerty

mine for $1 million, he was killed while

riding in a runaway stagecoach. The accident

happened on the aptly named Snow Slide Hill

on his way home from the mine in Encampment.

Newspaper accounts of the time say

that his stagecoach was passing an area

where a team of horses had been killed by an

avalanche the prior year and the stench of

the dead bodies terrified the stagecoach’s

team of horses. Ferris was in the stagecoach

with a brother, who escaped unharmed. But

Ferris was tossed and hit a brake block and

brake beam on the wagon as it was

overturning.

“There is something

singularly pathetic in the death of Mr.

Ferris, and it furnishes a theme for the

moralists who like to discourse on the

vanity of life and the rewards that often

come from a life of toil too late to be

enjoyed,” a newspaper obituary at the time

read. “Having spent all his years seeking

wealth, Mr. Ferris finally attained it in a

way that has made his name famous all over

the land, only to have the reward snatched

from his hands on the very day of his

triumph.”

If his death had been

pathetic, what came next could certainly be

considered inspiring.

His wife Julia

announced that she would complete

construction of the Ferris Mansion, a Barber

and Klutz home likely sourced from the book

“Modern Dwellings,” which was published in

1888.

Barber was serving a nouveau

riche clientele who had made fortunes out

West and wanted homes that made a statement,

not only about their success, but about the

success of the West.

The cost for

Julia to complete the spacious 21-room,

three-story home with 65 windows and five

fireplaces was in the neighborhood of

$60,000 in 1900 dollars, plus an additional

$25,000 for the furnishings, which she

sourced from San Francisco. A glass

chandelier in the home itself cost $1,000.

Colorado-pressed brick custom-designed

for the home was used to form the home’s

18-inch-thick walls, which had an air space

in the middle. Local sandstone was used to

trim between the bricks, as well as the

granite base of the home.

The roof

tiles were interlocking ceramic Ludiwici

tiles with a lifespan of 100 to 300 years.

Do

you have information you'd like to share? Or would you

like to help us?

Please

volunteer

to help the WYGenWeb Project.

The

WyGenWeb Project

Colleen

Pustola,

State Coordinator

Rebecca

Maloney,

Assistant State Coordinator

AVAILABLE

– County

Coordinator

Being

a County or State Administrator is fun and rewarding. If you

have an interest in the history of Wyoming and the genealogy

of it's residents please consider it. If you think "there

is no way I can do this" there are many people ready,

willing and able to help you. It's not near as difficult as

you might think.

|